Exploring eBPF: From Packets to Programs

I first came across eBPF when configuring the Container Network Interface (CNI)

for Kubernetes,

choosing Cilium as the solution, and became curious about how it

actually differs from other popular CNIs like Calico (which now also has an eBPF mode to eliminate kube-proxy).

Unfortunately, I never had the chance to work with or develop an eBPF program directly, until now.

In this post, I’ll go over my early learnings, and plan to share

more hands-on experience with well-known tools and languages in the future.

If you’re also into eBPF and its ecosystem, you probably know there’s already a huge amount of content online. So why write another one? This post is more like a collection of the questions I had and all the trial-and-error moments during my learning process. Hopefully the way I organize things here will help someone who learns similarly.

Since I mentioned learning resources, let me share a few that I found helpful:

- Yes, eBPF do have an official website with rich content. So does its Wikipedia page.

- This documentary-style film is an interesting introduction, telling the story from the innovators themselves.

- Brendan Gregg is one of the pioneers featured in above film. He’s blog is full of detailed demos and visual explanations.

- As I started with Cilium, I also explored resources form its creator company, Isovalent, which offers tutorials ranging from basic eBPF to advanced Cilium functionalities.

What is eBPF?

It stands for extended Berkeley Packet Filter. So, what is BPF in the first place? BPF was introduced in 19931. As its name suggests, it was originally designed to efficiently filter network packets. It provides the instruction set that runs on a 32-bit RISC CPU and directly manipulates registers to apply filtering rules. This avoids wasting time and resources copying packets from hardware into kernel and user space, because many of them can be dropped much earlier in the process.

Around 10 years ago, eBPF was presented originally to solve SDN-related problems2 using the similar concept to BPF, But the vision quickly become broader: to safely offload and run custom programs inside the kernel – using normal programing languages and compilers – without modifying the kernel itself. If the idea still feels vague. Some people also explain it by saying things like, “It’s like putting JavaScript into Linux kernel”3 or “it is a VM inside the kernel”4. When I first saw the JavaScript analogy, I thought: “Okay, so the kernel is like the browser that executes eBPF code easily.” But then I saw “VM”, as a systems person, that made me pause for a moment. After digging deeper, I realized that eBPF’s “VM” is closer to the idea of JVM or WebAssembly; not a cloud-style virtual machine that virtualizes an OS.

Yet, there is still some confusion in the naming

Sometimes I care too much about naming and where it comes from.

While looking into eBPF libraries and tools, I noticed that many of them are just named with bpf

(e.g.,libbpf and bpftool).

Based on Liz Rice’s book, Learning eBPF,

the community is aware of this ambiguity,

eBPF tends to be used in more commercial or user-facing contexts,

while bpf is widely used in technical implementation.

Nevertheless, I would still use “eBPF” in this post.

On the other hand, the original paper used “BSD” in the title, but later discussions started using “Berkeley” instead – not to tie it to a specific OS anymore, but to honor the actual origin of the work and reflect its broader evolution. By the way, the “B” in BSD also stands for Berkeley, since it was originally developed at the University of California, Berkeley.

How eBPF Works?

Let’s briefly illustrate the lifecycle of an eBPF program.

- Write the codes with eBPF libraries (e.g. libbpf) or frameworks (e.g. BCC).

- Compile the program into eBPF bytecode using Clang/LLVM in user space.

- Load the bytcode in kernel using the

bpf()system call. This process involves:- Bytecode is first sent to the verifier to check if it can safely run in kernel.

- If it succeeds, the bytecode is optionally passed to the JIT compiler for transilation into native instructions and further architecture-wise optimization; otherwise, it is executed through the kernel interpreter. The JIT compilation method is dominant due to performance advantages.

- Then the program is attached to the specific kernel hook point.

- Now, the eBPF program executes inside the kernel automatically when the corresponding event or trigger occurs.

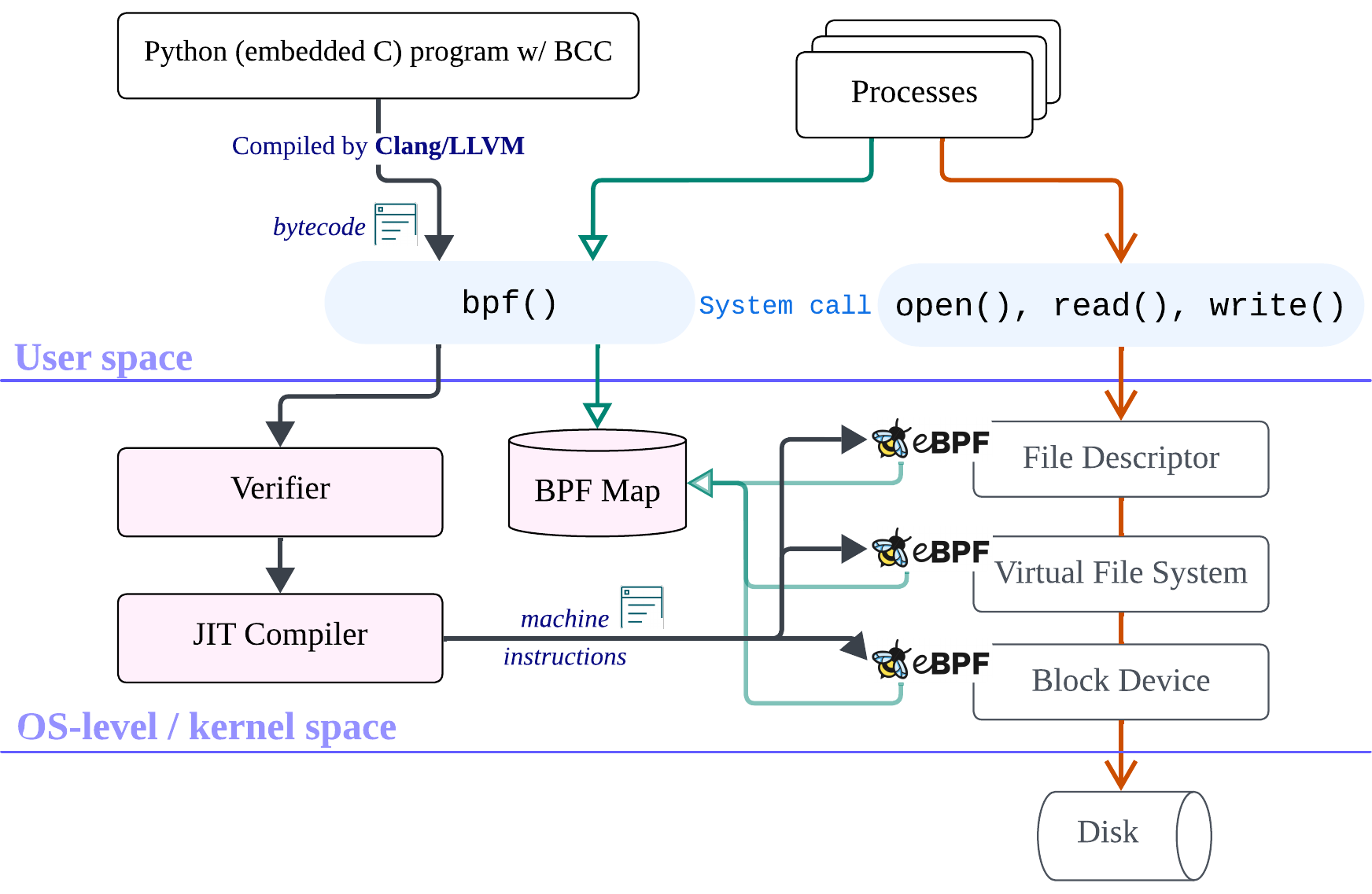

The processing steps described above are demonstrated by the black arrows in the figure below.

The processing flow of deploying the eBPF program (black arrows), the eBPF map access flow (green arrows), and the event-driven execution flow that triggers eBPF functions (orange arrows).

In this figure, I show an example where BCC is used to develop eBPF programs for introspecting file I/O behavior. The exact development and deployment methods, hook points, and functionalities vary depending on the use case and are not limited to this example. In practice, eBPF programs can be attached to many parts of the kernel.

Although an eBPF program is not a daemon and only runs when triggered by events,

we still need to understand how to unload it (the lifecycle doesn’t really end at step 4 😆).

As with any application or service, we can manage the detachment using the same bpf() system call

by closing the file descriptor returned by the BPF_PROG_LOAD operation

(see the manual for details).

The libbpf library also supports this through the related function.

Alternatively, we can use command-line tools such as bpftool

to remove a program from the kernel as this.

Next, I want to deep dive into some crucial discussions and techniques around eBPF.

eBPF program is not a kernel module

Kernel modules are commonly used to extend Linux functionality, for example, hardware drivers (you’ll definitely need one when installing a new Nvidia GPU on your computer) or popular system components like SELinux and KVM. These modules operate with high privileges and deep access to the kernel. For someone familiar with Linux, this might make eBPF sound similar: it also adds new capabilities to the kernel without modifying its codebase and can be loaded or unloaded dynamically.

One key difference between an eBPF program and a kernel module lies in how they ensure kernel safety5. Writing a kernel module requires deep kernel knowledge and strong credibility, since a faulty module can easily crash the system, or even damage hardware. That’s why developing and distributing trustworthy kernel modules is mostly limited to experienced developers or well-established vendors. The secret sauce behind eBPF’s safety is the verifier inside the kernel. It inspects every eBPF program before execution to make sure it won’t perform unsafe operations or compromise the system. Once your eBPF program passes verification for a specific kernel release, you can deploy it confidently on the hosts with the same version. Users can also feel more at ease knowing the verifier is built into the Linux kernel itself and maintained by the community6.

Just-in-Time (JIT) compilation

What does JIT mean, and why does the eBPF subsystem need it? A Just-in-Time (JIT) compiler isn’t new, the one in JVM is probably the most famous example. It sits between a standard compiler and an interpreter, combining some of the strengths (and weaknesses) of both.

Standard compiler/Ahead-of-time compilation: Translates human-readable source code into machine instructions. During compilation, architecture-specific optimizations occur, such as using special instruction sets or aligning memory. But once compiled, the binary is tied to that architecture; to run it elsewhere, you must recompile.

Interpreter: Executes code line by line directly without producing a separate binary, reducing build time. Interpreters work for both high-level source code (like Python) and for bytecode, as mentioned earlier, the kernel includes an eBPF interpreter. However, it runs slower because translation happens at runtime and no hardware-level optimization is applied. Errors also tend to appear only during execution.

JIT compilation takes a hybrid approach: it first compiles the code into bytecode, then translates that bytecode into machine code at runtime. In Java’s case, this design improves portability. Developers can compile once, and any platform with a compatible JVM can run the program.

For eBPF, JIT serves a different purpose: kernel safety, again. The kernel cannot fully trust compilers from user space, so it doesn’t execute user-compiled machine code directly. Instead, eBPF programs are first verified in their bytecode form (see the black flow in the figure). Only after passing the verifier does the kernel’s own JIT compiler translate that bytecode into native machine code for execution.

Clang/LLVM

In the eBPF deployment process (as shown in the figure),

another essential component we haven’t discussed yet is Clang/LLVM (not the hot LLM 🙈),

they work together to compile source code into eBPF bytecode.

Despite its name origin, LLVM (Low Level Virtual Machine) is no longer directly related to virtual machines.

It has evolved into a large umbrella project providing a collection of compiler and toolchain

technologies for generating intermediate representations.

The eBPF bytecode is one such target.

Clang, one of the subprojects under LLVM,

serves as the compiler frontend for the C language family (e.g., C, C++, and Objective-C).

The notation “Clang/LLVM” represents the cooperation between the frontend (parsing and syntax analysis)

and the backend (generating the target machine or bytecode) in the compilation process.

CO-RE mechanism

In the figure, the high-level eBPF program is written in Python using BCC. In this framework, we still implement the core logic in C and embed it as a string inside the Python script. The nice part is that the BCC library provides convenient abstractions for both bytecode compilation and kernel interactions (such as accessing eBPF maps or loading programs into specific hooks). Once the Python program runs, compilation, verification, and loading happen automatically. It’s a beginner-friendly way to explore kernel instrumentation without worrying much about deployment details.

However, BCC-based programs have low portability. One thing is obvious: because of its automated design, we need to pack everything necessary (libraries and compilers) onto the production machines – and still risk crashes at runtime (a-ha, and we only find out after running!). The other thing, which isn’t BCC’s fault, is that eBPF programs often rely on kernel data structures and functions that differ across kernel versions. These differences affect memory layouts, meaning the program usually needs to be recompiled for each target kernel. This repeated compilation increases deployment cost and limits portability.

To solve this, the CO-RE (Compile Once - Run Everywhere) approach was designed to generate portable eBPF bytecode by taking kernel type information into account during compilation. Instead of compiling from source on every production machine, we can prebuild CO-RE bytecode that adapts to different kernels. Then, production systems only need the precompiled bytecode and an eBPF loader (e.g., one built on libbpf) to load it into the kernel - the verifier step still applies. This approach significantly reduces overhead, since we no longer need to bundle the entire Clang/LLVM toolchain with each deployment and can save compilation time during delivery.

Here is the detailed explanation by Andrii Nakryiko, the developer behind CO-RE, perfect for people who wants to learn more.

More concepts and techniques not covered yet

There are still many design choices behind and around eBPF. I chose not to discuss them here, as they become more relevant once you start building eBPF programs or focus on specific domains such as networking or security. Still, I list some of them below as useful keywords for further exploration:

- Different hook points in the kernel: kprobe, tracepoint, etc

- Working with

bpftool - eBPF maps: shared data structures bewtween user space and kernel space. User-level processes interact with them through system calls (the green lines in the figure).

- Tail calls

- CO-RE related files: kernel header (

vmlinux.h), BTF data, and ELF - XDP (eXpress Data Path)

- eBPF on Windows

What’s Next

While writing this post, even though I had an outline and tried not to “come in like a lion, go out like a lamb”, I still found it growing too long in the middle - so I’ll stop here 🫣 to keep it focused on a few key perspectives.

My plan with eBPF is to explore its observability power and understand its limitations. I also hope to not only learn new tools but put Rust into real practice along the way.

The BSD Packet Filter: A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture ↩︎

PLUMgrid: https://www.linux.com/news/plumgrid-open-source-collaboration-speeds-io-and-networking-development/ ↩︎

What does Brendan say: https://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2024-03-10/ebpf-documentary.html ↩︎

The VM concept: https://www.tigera.io/learn/guides/ebpf/, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/ebpf/ ↩︎

eBPF - Rethinking the Linux Kernel, Thomas Graf’s talk describes more details about differences between kernel module and eBPF program. ↩︎

The verifier isn’t an all-seeing superhero. That’s why projects like PREVAIL and VEP exist. ↩︎

Author Carol Hsu

LastMod 2025-11-13 (6e67d46)

License All rights reserved. Feel free to reach out with any questions.