Networking in Kubernetes

One day during a lunch gathering in my PhD, my advisor asked: If you weren’t doing systems, what other research area would you choose?

My first pick was network. Why?

People often say we enjoy things we’re good at, because the small wins keep us motivated: you do well, you don’t get frustrated often, so you naturally want to do more. If that logic held for me, I should’ve been great at team sports. I enjoyed volleyball, baseball, and basketball, but honestly, I’m pretty sure no one wanted me on their team 🤣. And I’m not especially good at network techniques either. But when I run into network configuring issues, I don’t get stressed or annoyed; I just want to understand what’s going on (machines don’t fail for no reason, humans usually caused it). That’s probably the first spark that made me think projects related to network could be fun to explore.

Instead of picking a research direction from scratch, most opportunities grow out of nearby, familiar ideas. And that’s basically the starting point of this post. I’m going to talk about Kubernetes networking, mainly as a way to clean up my own understanding and catch up on newer ideas1. I also think this knowledge base can serve as a foundation for exploring some interesting networking questions.

In this post, I’ll walk through the Kubernetes network stack from bottom to top, starting with the more infrastructure-wise configurations and moving toward application- and workload-level management.

Kubernetes and Its Network Model

Kubernetes (K8s) is a name from ancient Greek, κυβερνήτης, meaning someone who gives the commands. It was from Google, now a famous, open-sourced container orchestration system. By saying K8s orchastrating or managing containers, we have a set of computation resources, e.g., a cluster of machines, and many applications in the microservice structure, K8s is the software in the middle/linkage of these two groups: it helps to deploy and support the containers running on the machines with sufficient resources and proper isolations.

Networking within K8s and with external endpoints is one of the important domain of study and management in system perspective.

Here are some fundamental K8s keywords/abstractions that might help before moving on. You can skip this if you already know them well.

Namespace: Similar to Linux kernel namespace. They isolate or separate things from permissions, resources, compute units into groups. Components in different Namespaces can still share resouce or interact with each other if access is configured accordingly.

Pod: The smallest compute unit in K8s. A Pod has an IP assigned by Container Network Interface (CNI) plugin, which means all containers inside the Pod share the same IP and they work as processes in single host so can communicate just through

localhostwith each others.Service: The abstract networking endpoint for an application or function. The K8s API server (

kube-apiserver) allocates a virtual IP to each Service. A Service covers a groups of Pods using labels. Service is the essential idea for microservice-style deployment and enable features like scaling and traffic control.

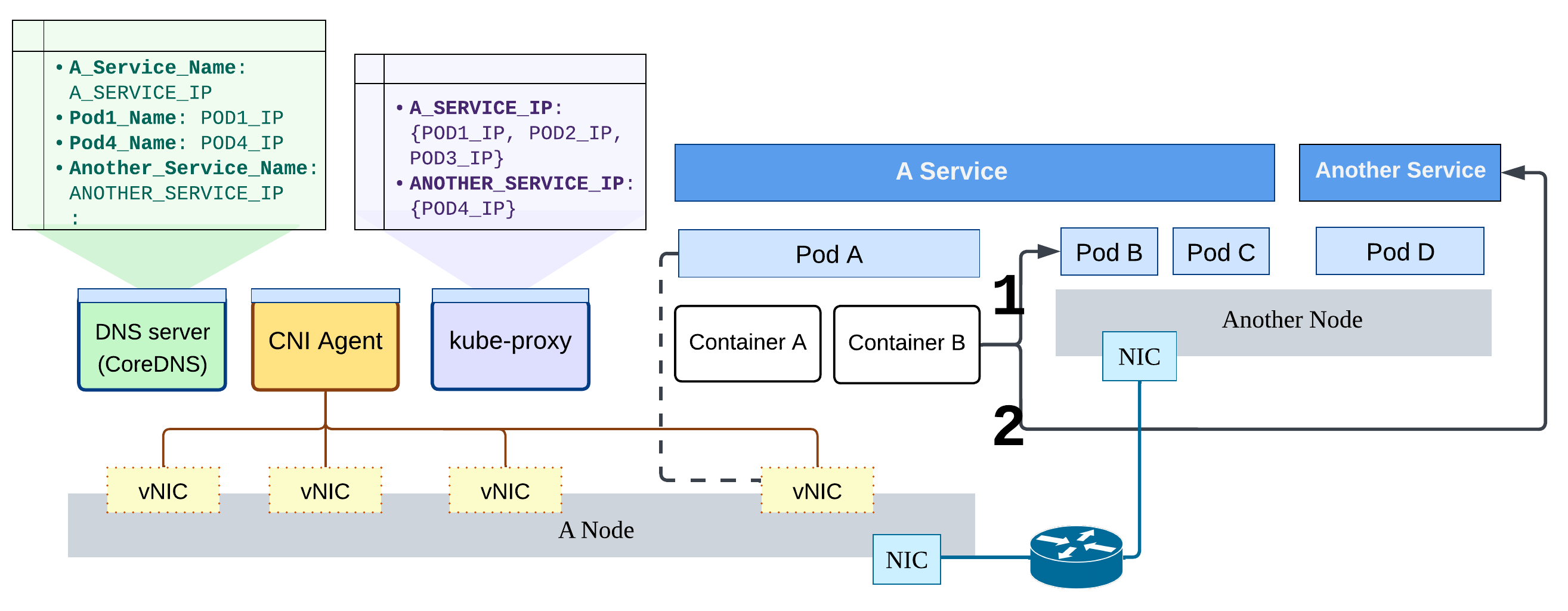

The right side of the diagram below demonstrates that both Pods and Services can contain multiple containers or multiple Pods. Pods within the same Service don’t need to run on the same host. K8s (scheduler) balances the workload across the cluster.

To avoid confusion, K8s terms are usually capitalized when written out. “Service” particularlly is so common that I always say “Kubernetes Service” in coversations to make it clearer.

The diagram above demonstrates two main discussions:

On the right part: how does the application, packed in containers, communicate with the other internal workload? Two ways through Pod or Service, they can interact via their IPs and domain names.

On the left part: there are three key control-plane networking components. They also run as containers, which means they are physically co-located with user workloads, and just managed in separated Namespaces (e.g. the user-defined “production”, or the default “kube-system” for system components).

Then, the next question is, how do these components enable and coordinate the intra-cluster communication?

Accessing through IPs

When accessing a workload with a Pod IP or a Service IP, traffic is guaranteed to reach the same target application (although possibly by different endpoints). The IPs between Pods and Services are managed and behave differently.

Each Pod is assigned a virtual NIC in the cluster network, which is managed by the CNI plugin. If a packet’s destination is outside the local subnet of the host, it is forwarded to other hosts in the cluster (#1 in the figure). This should sound familiar – it closely resembles how traditional computer clusters work. Based on the host’s routing rules, packets destined outside the cluster are encapsulated and sent through a gateway or head node, typically using NAT.

You can think of this as a series of analogies:

- Pods on the same host vs. machines in the same cluster

- Pod IP vs. private IP in the cluster

- Pods on other hosts vs. external endpoints

- CNI-managed network vs. the public Internet

Because of these similarities, many CNI implementations reuse well-established networking techniques like BGP and VXLAN.

Service IPs, on the other hand, act more like references that only exist within the K8s cluster. A Service represents a logical workload, which is actually backed by a dynamic set of Pods. These Pods can scale up or down without affecting clients2. Using an IP abstraction simplifies communication: from the client’s perspective, it looks like talking to a single, normal component, just like any other service on the Internet. From the networking side, packet forwarding can be implemented using existing mechanisms such as iptables and netfilter.

The kube-proxy component runs on every K8s Node and is responsible for maintaining

the IP and port mappings between Services and their backend Pods.

This role can be replaced by other implementations that take over the same responsibility.

Accessing through the domain names

K8s also provides DNS-based access to Pods and Services using CoreDNS.

To make internal name resolution work (as shown by #2 in the diagram), two main processes are involved.

First, when Pods or Services are created or removed,

CoreDNS updates the corresponding DNS records, both in backing storage and in-memory cache.

Second, on the client side, when a container starts, the kubelet configures its DNS resolver settings

(e.g., /etc/resolv.conf).

As a result, queries for local domain names are automatically directed to internal CoreDNS.

For a deeper understanding of this process,

the official documentation has detailed explanations of DNS name formats and server configuration.

Exposing Services to the world

To make a Service accessible to external clients, the simplest approach is to set its type to NodePort.

This exposes the Service on a fixed port, by default in the range 30000 to 32768, on every node in the K8s cluster.

Yes, this is not a typo: the port is opened on every node,

with traffic forwarding managed by kube-proxy.

While this allows external clients to reach the Service through any node and provides basic load distribution,

it also introduces security risks and operational redundancy.

Therefore, the NodePort Service is rarely the final step in a production system design.

In practice, it is typically combined with other K8s resources

to build a more robust and elegant way of exposing workloads publicly.

We will explore these options in the later sections.

Traffic Control Enforcement

Now we understand how accessibility and service discovery work in K8s,

and these connections are preconfigured and supported by the system.

What if we want to do the opposite – to block or restrict certain traffic?

This is where the NetworkPolicy

resource comes in. NetworkPolicy relies on CNI support to be enforced on Pods.

Each NetworkPolicy defines ingress and/or egress rules

and applies to Pods selected by labels.

When using NetworkPolicy, there are several important features and limitations to keep in mind:

Pods become default-deny once a policy applies: When any rule is set on a Pod, it becomes isolated. In other words, NetworkPolicy defines only allowable traffics.

Traffic on the Node is not filterable: Traffic originating from the same Node (e.g., kubelet or host-networked components) is not affected.

Implicitly allows response traffic: When ingress/egress traffic is allowed, the corresponding response traffic is automatically permitted. It doesn’t need to be defined explicitly.

Policies have no ordering and are unioned: There is no sequence in policy enforcement. All applicable rules are combined, and traffic is allowed if any rule permits it.

When to set NetworkPolicy for a service?

Conceptually, NetworkPolicy provides internal network isolation. We can call it this way because originally Pods can communicate with any other entity in the K8s cluster, while external access requires additional exposure configurations. NetworkPolicy changes this default by enforcing explicit connectivity constraints. From a service delivery perspective, clear network separation helps prevent mistakes such as staging components accessing production databases, and reduces the problem space during debugging. NetworkPolicy is also useful for building a secure networking environment. For example, acting as a last line of protection by allowing traffic only from whitelisted CIDR sources to public-facing Pods.

Load Balancing Implementation

The load balancing discussed here focuses on network-level: how incoming requests are distributed across multiple compute instances to achieve efficient resource usage and low latency. K8s Service abstraction is a core building block for scalability and basic traffic distribution. When multiple backend Pods run across different nodes, a Service can spread incoming requests among them. However, this doesn’t guarantee well-balanced load at the Pod level. Additional system components are required, as a vanilla K8s has no sophisticated load-balancing mechanisms.

How it works in public clouds?

You might then ask: what is the purpose of the LoadBalancer Service type?

The LoadBalancer type exists primarily to simplify integration with public cloud environments.

There are necessary K8s APIs

so cloud providers can propagate load-balancing configuration

and correctly bind the external load balancer to the Service.

Internally, a LoadBalancer Service is implemented

the same way

as a NodePort Service.

The external load balancer simply forwards traffic to the assigned ports on cluster nodes.

This method allows traffic to be distributed across hosts, but it also inherits the same limitations as NodePort. In particular, a request may reach a node that does not host any target Pods, requiring additional forwarding at the node level. True endpoint-level load balancing (traffic is sent directly to Pods) avoids this inefficiency. Popular cloud providers ( AWS and GCP, I could not find a similar implementation in Azure at the time of writing 🫣) do support this model.

Which approach is better? No universally best setup, I would say. There is another form of load balancing at a different layer: the scheduler, which balances workloads across cluster resources rather than balancing incoming traffic. In practice, load-balancing strategies should be chosen case by case. Optimizing for end-user performance while maintaining system resilience and adaptability to new requirements and techniques remains a long-term design goal.

Application-level Traffic Management

A comprehensive system is often complex because it has to address multiple concerns at once. Like exposing a service, opening ports and configuring listeners is usually not enough. We also need to consider communication protocols, access permissions, security settings, and observability, taking them into consideration simultaneously, and sometimes more.

Decisions about these aspects typically depend on the application’s workflow and functionality. That means designing a service is not only about implementation details, but also about who is responsible for each part of the process. (I’ll skip discussing ownership here, as it’s more related to organizational structure and service scale.) To take service exposure and traffic management to the next level, there is an additional resource type, Gateway, and the well-known service mesh solutions. Let’s take a closer look.

Gateway API

Gateway is a plugin feature in K8s. Similar to CNI, there are many implementations you can install in your cluster. Each solution typically provides a controller that executes Gateway functionality (some also create the related CRDs automatically). But, their exact mechanisms are diverse. Like, Cilium integrates control and configuration functions inside its CNI; NGINX Gateway Fabric enforces HTTP/TLS rules without using sidecar components; and Istio leverages its original service mesh (no worry, we will talk more later) architecture.

The Gateway API itself is structured as a set of cascading configuration objects for ingress traffic: GatewayClass, Gateway, and Route. A GatewayClass indicates which the installed Gateway controller. A Gateway picks a GatewayClass (and therefore a controller) and defines connection settings such as domain name, port, protocol, and TLS configuration. Routes bind backend Services to the Gateway with target ports and access paths.

The passing-away Ingress

The Gateway API didn’t appear overnight: it was introduced as the evolution of the existing Ingress API, which is now a “frozen” feature. During this transition, many components and configurations must be carefully planned for migration. For example, projects such as Ingress NGINX have announced retirement as the ecosystem gradually shifts toward the Gateway API. Nevertheless, users are not necessarily rushing to adopt Gateway immediately. Not all Gateway API features are fully stable yet, and production environments often prioritize reliability over novelty. As a result, many teams find themselves in a transitional state: aware of what is coming next, prepared for change, but need to find a good timing to fully embrace it.

This situation highlights an often-overlooked aspect of system maintenance: lifecycle management. At times, maintaining a healthy system requires migrating core components to newer alternatives to avoid relying on outdated or vulnerable technologies. This responsibility is impactful, technically demanding, and frequently underestimated.

Service mesh

When discussing application-level traffic management in K8s, it is hard to ignore service mesh. Service mesh is not a concept exclusive to K8s, its popular solutions are like Linkerd and Istio. It originated as an architectural idea in microservices, aiming to move connectivity concerns, such as routing, retry/timeout, and security, from source code into the infrastructure layer. K8s did not invent service mesh, but it significantly accelerated the adoption of microservices, which in turn made service mesh solutions more relevant. Even if K8s were to disappear in the future, as long as applications continue to follow a microservice model, service mesh techniques would still have a role to play.

Applications built with a microservice architecture (discussed in more detail in my another post) typically involve much heavier inter-service communication than monolithic applications, because they collectively function as a single workload. To handle this complexity, a service mesh offloads networking responsibilities by introducing a proxy alongside each microservice. All inbound and outbound traffic for a microservice passes through its dedicated proxy, allowing networking logic to be handled centrally at the proxy layer rather than in application code. In addition, the mesh formed by these proxies can monitor runtime communication behavior, significantly improving the application’s network-level observability.

Is Gateway API able to replace service mesh?

Perhaps. Although the Gateway API is still evolving, it already overlaps with service mesh in its capabilities. In theory, if a deployment uses a sufficient number of Gateways and Routes, they could act as distributed proxies for microservices. The community has recognized this convergence, which led to working group like GAMMA initiative, exploring how Gateway API concepts can be used to configure and manage service mesh behavior. Yet, the Gateway API is not intended to manage service-to-service communication. Although combining it with service mesh concepts may simplify configuration, it shifts additional complexity and workload onto the control plane.

Looking Back and Forward

In this post, I intentionally kept Kubernetes abstractions, terminology, and components to a minimum to keep the focus on networking. I hope it has drawn some insight or interest in Kubernetes networking.

Let’s jump back to the very beginning of this article. Doing a PhD can sometimes feel like gambling: you invest many years working in a relatively narrow domain, immersing yourself deeply to eventually become an expert. Along the way, it’s natural to question whether you chose the right research topic, or to worry that you’re spending time on something that may not be fashionable. This kind of doubt and pressure can arise even when you know you’re working on something you genuinely enjoy.

By the way, I’m always happy to have coffee chats about why and how I did my PhD. If you’re considering a PhD or already on that path, feel free to reach out.

Unlike my last eBPF post, where I read many materials from different sources online, added tons of reference links, and still worried I might sound like a copycat. For this one, I mainly checked the official docs just to make sure things are up-to-date, and feel more confident that everything here is written in my own words. The challenge part is how make this article more fun to read 😓. ↩︎

EndpointSlice resources are created automatically when a Service specifies certain backend Pod(s). You can also configure it for a more fine-grained scaling management. ↩︎

Author Carol Hsu

LastMod 2026-01-17 (b949a62)

License All rights reserved. Feel free to reach out with any questions.