LeetCoding as a Routine

This post isn’t about how to win anything with LeetCode. It’s just a collection of my thoughts (and maybe some complaints), along with notes that are probably only useful to me.

I don’t need to introduce LeetCode — it’s already well known for its massive database of coding challenges and technical questions. Many candidates use it to prepare for interviews in software engineering and related fields. Still, there are some ethical gray areas with platforms like this:

How are the questions collected? How do they find out which interview problems are used by which companies?

They do make money. While users openly share solutions and discussions, arguably the sweetest part of the platform, is there any kind of reward system for those who contribute the most?

Candidates can ace a question quickly in an interview simply because they just practiced a nearly identical one.

Maybe that’s why LeetCode has become a sort of “He Who Must Not Be Named.” When companies send out coding interview instructions, they often reference other materials. But in reality, most well-prepared candidates use LeetCode behind the scenes.

Why Do I Start Doing LeetCode Every Day Recently?

Compared to senior software engineering roles, the positions I’m aiming for don’t seem to emphasize coding interviews as heavily, in terms of time pressure or difficulty. I’ve heard that competitive engineering roles often involve 3~5 rounds of intense coding tests. So, why do I practice LeetCode daily?

Well, simply because I enjoy it. I like brainstorming and solving problems. Before LeetCode, I spent time on Project Euler and CheckIO with Python. I switched to LeetCode about a year ago for a few reasons (I still play some on the other two):

- Time: I started dedicating more time to coding challenges, which made me want to try harder or more varied problems. But I also needed a way to limit how much time I spent on each one. That’s where LeetCode helps: the Daily Challenge and Weekly Contest — I aim to finish a problem within a day or solve several in 1.5 hours during contests. It keeps things balanced and time-boxed.

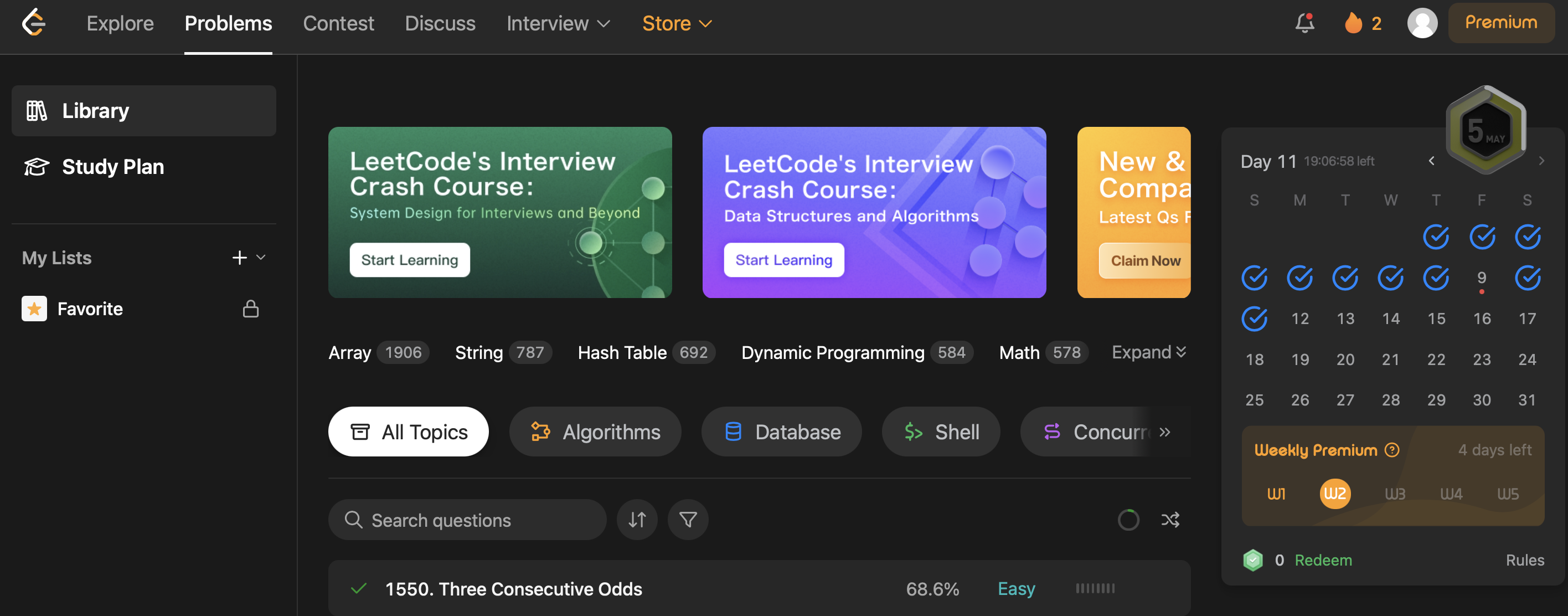

LeetCode Daily Challenge tracks the streak and motivates me to check in every day. The daily problem appears at the top of the list. For example, today's is No. 1550.

Community: LeetCode has a huge user base. Even if I don’t actively post or answer questions, reading through other people’s discussions really helps clarify my thinking when I’m stuck. And since there’s rarely single solution, exploring different approaches helps me grow.

Challenging test cases: Because LeetCode is designed with interviews, brute-force solutions often fail. If you write something naive, you’ll probably get hit with a follow-up like “What if the input is huge?”. The platform expects you to understand space and time complexity, and to improve your solution accordingly. I like that challenge — it’s not just about making it work, but making it better.

Sounds intense, right? Don’t worry, I set boundaries. I know there are lots of other important or interesting things I need to do every day, so I don’t go all in. For example, as you can see in the screenshot above, I skipped the problem on the 9th, because I still cannot figure it out. That’s my limits 😆.

How Hard Do We Really Need to Grind for Interview Tests?

LeetCode problems are designed to be solved quickly, unlike the problems in contests of the cancelled Google Code Jam or the Olympic-level ACM ICPC. Some people prepare extremely hard, solving hundreds of problems to build muscle memory: “Ah, I’ve seen this pattern before – I’ll just apply that trick.” Even though I’m currently job hunting too, I don’t agree with that approach. Why? Because it’s kind of insane. I want to code for fun, not for the sake of passing a flawed interview process.

Sure, being able to solve LeetCode problems quickly and accurately shows that you’ve worked hard to prepare. But that doesn’t directly prove you’re a good engineer. There’s a lot more that matters: real-world technical skills, how you think, how you communicate, and most importantly, whether you’d be a good teammate.

When practicing for coding interviews, I try to keep the following key principles in mind:

Be fluent in your chosen language: know the syntax well, and only use packages or libraries you understand thoroughly (because you might be asked how they’re implemented).

Understand the problem: make sure the input, output, and edge cases are all clear to you.

Write clean code: use clear naming, proper formatting, and choose efficient, appropriate data structures.

“Wait, don’t you need to practice specific algorithms?” Of course we should. But as I said earlier, doing algorithm practice without structure or focus feels pointless to me, like a headless chicken running around. Just doing lots of problems without reflection doesn’t help much. Instead, we should build a solid foundation. It is already not easy to meet the principles above. During the interview, we need to show that we can write clean, thoughtful code in our language of choice, and engage in deeper discussion about algorithms and data structures, especially in relation to principle #2. That’s the kind of interview I think is worth aiming for.

Problem Solving

Here are some common methods or algorithmic patterns I often use to solve LeetCode problems. I’m sharing them as notes:

Key methods summary

- Dynamic Programing / Memorization / Recursion

Recursive solutions are often the most intuitive way to approach problems with large state spaces,

but they can easily lead to stack overflows or timeouts.

That’s where dynamic programming (DP) comes in.

DP is about storing intermediate results (memoization)

so we don’t recompute the same things again.

Many recursive problems can be rewritten using DP to improve efficiency.

For a problem with N dimensions, we usually use an N-1 dimensional memory structure

to store computed values.

That said, once N reaches 3 or more,

the logic and memory usage can become complex and tricky to implement

(like this one).

Many people see DP as the final boss. The hardest part often is figuring out what variables you should index by, in other words, how to represent the problem state in a way that allows memoization.

- Prefix Sum

Prefix Sum is applied to work with subarray sums or aggregated values over ranges.

The idea is to precompute a total aggregation at each index,

so later you can compute the sum of any subarray [n, m] in constant time using

prefix[m] - prefix[n].

- Breadth-First Search / Depth-First Search

Breadth-First Search (BFS) and Depth-First Search (DFS) are algorithms for exploring tree or graph structures. You don’t always need to model a full tree/graph in code; what matters is the traversal strategy. BFS explores neighbors level by level (often with a queue); and DFS dives deep before backtracking (usually with a stack or recursion). Both are great for exploring reachable states, shortest paths, and connected components.

- Binary Search

Binary Search isn’t just for sorted arrays. It’s a powerful way to narrow down the search space in any problem where the space is monotonic. In other words, the solution space behaves in a way that allows binary decisions.

- Backtracking

When coding, things get tiring once the logic gets too complicated: not only does the developer feel overwhelmed, but the reviewer also struggles to follow. As a method to simplify logics, backtracking is a clever way to handle brute-force methods: mark a state, explore all possible next states, then remove the marker when backtracking. It’s basically recursion + DFS, and it’s often used for problems like finding number combinations.

Useful packages in Python

When solving problems in Python, I find that built-in functions and data types are often enough for most solutions. I rarely need to import many extra packages. Still, here are a couple of standard libraries I do use from time to time:

collections: Especially useful tools like

Counterfor frequency counting anddequefor efficient queue operations.heapq: Provides a heap implementation. While it’s convenient, we should still understand how the underlying algorithm works (see principle #1 above).

Side Notes

To be honest, my goal with LeetCoding is to collect those visual coins and redeem some goodies. If I ever earn enough, I’m definitely showing off the prize.

Happy Coding and Happy Mother’s Day!

Author Carol Hsu

LastMod 2025-09-01 (5598e71)

License All rights reserved. Feel free to reach out with any questions.